Osceola was named Billy Powell at birth in 1804 in the Creek village of Talisi, now known as Tallassee, Alabama, in current Elmore County. “The people in the town of Tallassee…were mixed-blood Native American/English/Irish/Scottish, and some were black. Billy was all of these.” He was born to Polly Coppinger, a Creek woman, and William Powell, an English trader. Polly was the daughter of Ann McQueen and Jose Coppinger. Because the Creek have a matrilineal kinship system, Polly and Ann’s other children were all considered to be born into their mother’s clan; they were reared as traditional Creek and gained their status from their mother’s people. Ann McQueen was also mixed-race Creek; her father James McQueen was Scots-Irish. Ann was likely the sister or aunt of Peter McQueen, a prominent Creek leader and warrior. Like his mother, Billy was raised in the Creek tribe.

Like his father, Billy’s maternal grandfather James McQueen was a trader; in 1714 he was the first European to trade with the Creek in Alabama. He stayed in the area as a fur trader and married into the Creek tribe. He became closely involved with the people. He is buried in the Indian cemetery in Franklin, Alabama near a Methodist Missionary Church for the Creek.

In 1814, after the Red Stick Creek were defeated by United States forces, Polly took Osceola and moved with other Creek refugees from Alabama to Florida, where they joined the Seminole. In adulthood, as part of the Seminole, Powell was given his name Osceola. This is an anglicized form of the Creek Asi-yahola, the combination of asi, the ceremonial black drink made from the yaupon holly, and yahola, meaning “shout” or “shouter”.

In 1821, the United States acquired Florida from Spain. More European-American settlers started moving in, encroaching on the Seminole. After early military skirmishes and the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, by which the US seized northern Seminole lands, Osceola and his family moved with the Seminole deeper into central and southern Florida.

As an adult, Osceola took two wives, as did some other Creek and Seminole leaders. With them, he had a total of at least five children. One of his wives was African American, and he fiercely opposed the enslavement of free peoples.

Through the 1820s and the turn of the decade, American settlers kept up pressure on the US government to remove the Seminole from Florida to make way for their desired agricultural development. In 1832, a few Seminole chiefs signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing, by which they agreed to give up their Florida lands in exchange for lands west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory. According to legend, Osceola stabbed the treaty with his knife, although there are no contemporary reports of this.[6]

Five of the most important Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminole, did not agree to removal. In retaliation, the US Indian agent, Wiley Thompson, declared that those chiefs were deposed from their positions. As US relations with the Seminole deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to them. Osceola, a young warrior rising to prominence, resented the ban. He felt it equated the Seminole with slaves, who were forbidden to carry arms.

Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend, and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola quarreled with Thompson, the agent had the warrior locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, to get released, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne’s Landing and to bring his followers in to the fort.

On December 28, 1835, Osceola led an attack on Fort King (near modern-day Ocala) which resulted in the assassination of the American Indian Agent Wiley Thompson. Simultaneously, Micanopy and a large band of Seminole warriors ambushed troops under the command of Major Francis Dade south of Fort King on the road to Fort Brooke (later Tampa). These two events, along with the Battle of Withlacoochee on December 31 and raids on sugar plantations in East Florida in early 1836, marked the beginning of the Second Seminole War.

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/4369

In late October 1837, Osceola contacted General Joseph Hernandez, through a black interpreter named John Cavallo (also John Horse), to arrange negotiations about ceasing hostilities. General Thomas Jesup responded by ordering Hernandez to seize Osceola and his party should he have the chance.

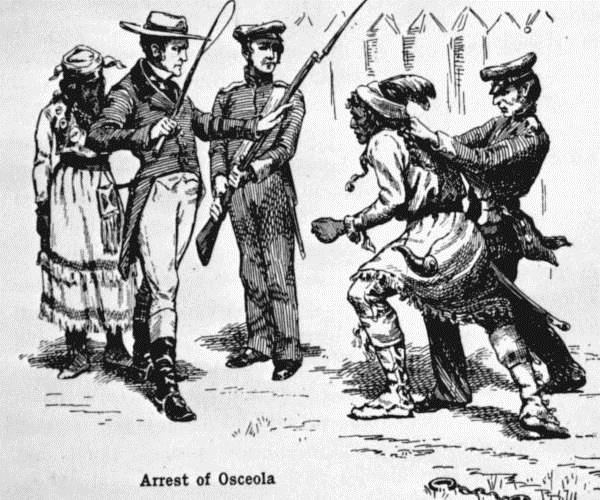

Osceola’s camp, located one mile south of Fort Peyton, raised a white flag of truce in order to signal their desire to negotiate. When Hernandez and his entourage reached the camp, they promptly seized Osceola and the warriors, women and children present. Osceola and his band were brought to St. Augustine and imprisoned at Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos).

Remarkably, on November 30, Coacoochee (Wildcat) and 19 other Seminoles escaped Fort Marion; Osceola was not among them. Coacoochee’s escape prompted Jesup to transfer the most important Seminole captives out of the area. In late December 1837, Osceola, Micanopy, Philip and about 200 Seminoles embarked from St. Augustine for Fort Moultrie on Sullivans Island, outside Charleston, South Carolina. After their arrival, they were visited by townspeople.

Osceola’s capture by deceit caused a national uproar. General Jesup and the administration were condemned by many congressional leaders.

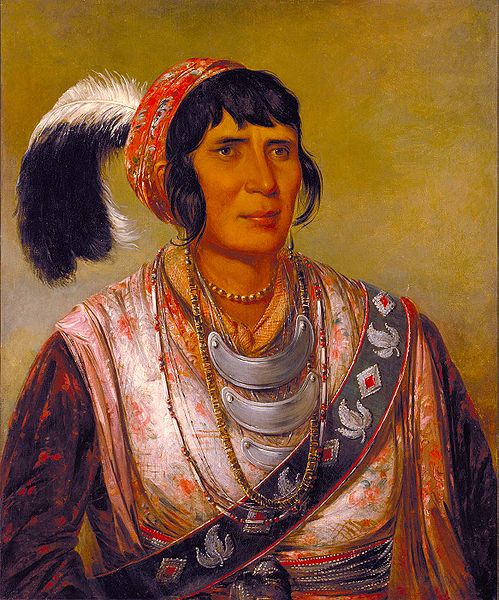

George Catlin and other prominent painters met the war chief and persuaded him to allow his picture to be painted. The painting above is by Catlin. Robert J. Curtis painted an oil portrait of Osceola as well. These paintings have inspired numerous prints and engravings, which were widely distributed, and even cigar store figures.

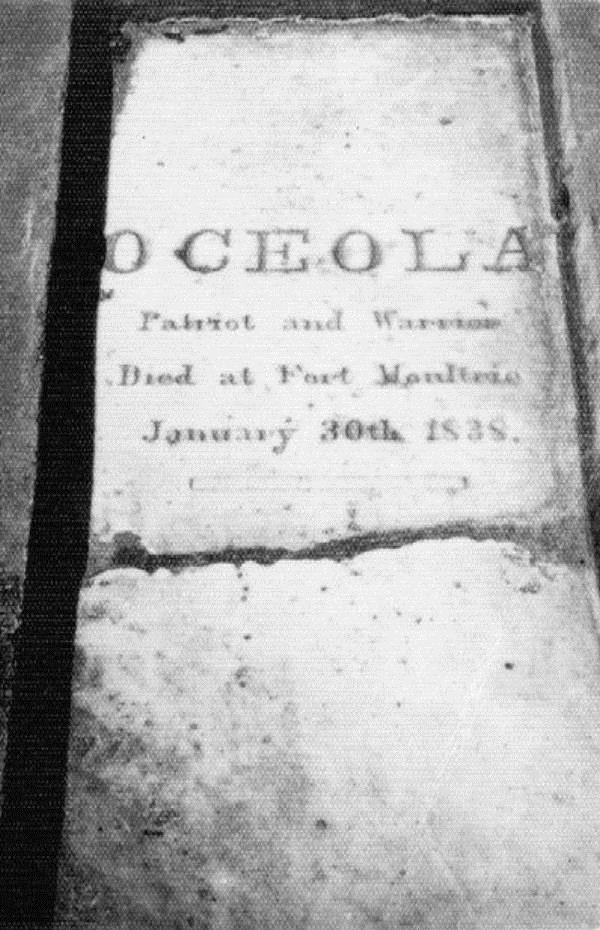

Osceola, who previously contracted malaria in Florida, became severely ill soon after arriving at Fort Moultrie. Osceola died of quinsy (though one source gives the cause of death as “malaria” without further elaboration) on January 30, 1838, three months after his capture. He was buried with military honors at Fort Moultrie.

After his death, army doctor Frederick Weedon persuaded the Seminole to allow him to make a death mask of Osceola, shown below, as was a European-American custom at the time for prominent people.

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/4299

Later Weedon removed Osceola’s head and embalmed it. For some time, Weedon kept the head and a number of personal objects Osceola had given him.

Later, Weedon gave the head to his son-in-law Daniel Whitehurst. In 1843, Whitehurst sent the head to Valentine Mott, a New York physician. Mott placed it in his collection at the Surgical and Pathological Museum. It was presumably lost when a fire destroyed the museum in 1866. Some of Osceola’s belongings are still held by the Weedon family, while others have disappeared. One of Chief Osceola’s possessions is shown below.

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/4294

Captain Pitcairn Morrison sent the death mask and some other objects collected by Weedon to an army officer in Washington. By 1885, the death mask and some of Osceola’s belongings ended up in the anthropology collection of the Smithsonian Institution, where they are still held.

Osceola’s grave marker says, “Osceola, Patriot and Warrior, died at Fort Moultrie, January 30, 1838.”

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, http://floridamemory.com/items/show/4295

http://www.kislakfoundation.org/millennium-exhibit/profiles6.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Osceola

http://nativeheritageproject.com/2014/03/15/creek-indian-mound-near-fort-decatur-alabama/

http://nativeheritageproject.com/2014/03/12/osceola-powell-seminole-chief/

http://floridamemory.com/blog/2013/01/30/osceola-ca-1804-1838/