Purchase yours today at Seminole Nation, I. T

Monthly Archives: August 2015

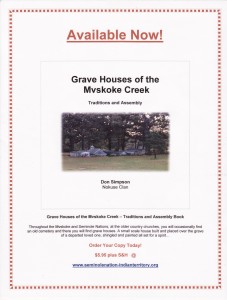

Grave Houses of the Mvskoke Creek – Traditions and Assembly Book

Throughout the Mvskoke and Seminole Nations, at the older country churches, you will occasionally find an old cemetery and there you will find grave houses. A small scale house built and placed over the grave of a departed loved one, shingled and painted all set for a spirit…

Coming Soon!

Grave Houses of the Mvskoke Creek – Traditions and Assembly Book

Look for details at Seminole Nation, I. T. to order your copy.

Mvto!

Edmund Harjo – Seminole Code Talker

During the dark, early days of World War II, American military commanders were desperate for a code that could not be cracked by the Japanese. The solution rested in the obscure languages spoken by Native American tribes, unfathomable to the Japanese. Native American code talkers, as they became known, were able to transmit messages quickly and securely, giving American forces a critical edge.

While the contributions of Navajo Code Talkers have been honored by Congress and featured in films, the role of dozens of other Native American tribes has been overlooked. But on November 21, 2013, Congressional Gold Medals, the nation’s highest civilian honor, were awarded honoring the service of hundreds of overlooked code talkers from 33 tribes.

Native American calls and whoops of pride echoed through Emancipation Hall when tribal representatives, some wearing headdresses or other traditional clothing, received the medals in front of an audience of hundreds. Few of the code talkers are still living, and only one was present for the ceremony.

Edmund Harjo, 96 a member of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, served as a radio man with the 195th Field Artillery Battalion in France. Harjo, who attended in a wheelchair and received an ovation from the audience said afterward that the honor was appreciated but belated.

‘If I was young, I would enjoy it,” he said.

It’s a long time coming, ‘said Leroy Shingoitewa, 71. a member of the Hopi Tribe who has several uncles who served as code talkers.

“When the came home, they didn’t talk much about it, ” he said. “Finally, it’s become known.”

The United States first used Native American code talkers during World War I in October 1918, when the country used Choctaws to transmit messages confounding to the Germans. The idea was reborn during World War II, when the Marine Corps recruited several hundred Navajos to serve in the Pacific.

The Army used Comanche to develop a secret code based on their language, while members of other tribes were assigned to special native language communication duty.

Estimates place the number of Native American code talkers who served in the two wars at more than 400, according to the Defense Department. The code talkers’ role was kept classified for many years. “They returned heroes, but without a hero’s welcome,” said Rep. Ron Kind (D-Wis.). Navajo code talkers, who served in the largest numbers, were awarded the gold medal in 2001 at a ceremony in the Capitol Rotunda presided over by President George W. Bush.

In subsequent years, congressional representatives from states with large Native American populations, including Oklahoma and South Dakota, pushed for recognition of other tribes. Congress passed legislation authorizing gold medals to other tribes in 2008, but it took years for the Pentagon to research which tribes were eligible because no central records about code talkers exist.

Tribes and nations honored include the Comanche, Cherokee, Sioux, Choctaw, Hopi, Kiowa, Creek, Oneida, Osage, Pawnee, Ponca, Pueblo,

Sac and Fox, Seminole, Apache, Crow, Tlingit, Chippewa, Menominee and Mohawk.

The code talkers “embraced their cultural heritage and used it to prevent highly sensitive wartime messages from being intercepted by the enemy, ” said Rep. Tom Cole (R-Okla.), a member of the Chickasaw Nation and co-chair of the Native American Congressional Caucus. More tribes could be added based on further research, but with the code talker numbers dwindling and their immediate families aging, officials decided not to delay further, according to congressional aides.

“It’s a great feeling down here,” said Robert Atchavit, a Comanche from Oklahoma, patting his heart.

New Ways to Trace Your Native Ancestry

BIA School Records

In the 1880s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established 26 non-reservation boarding schools in 15 states and territories for vocational education. The first federally funded off-reservation school was Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Created in 1879, it existed until September 1, 1918. More than 10,000 students from 140 different tribes from all over the United States attended Carlisle. One of its most famous alumni was Sac and Fox athlete Jim Thorpe (1888-1953), who won gold medals in the 1912 Olympics.

The National Archives holds many records about these BIA-operated schools and the students who attended them. Most of these non-reservation schools created and maintained a case file for each student. Family history researchers will discover that students were often sent to schools by the Indian Agency, which had jurisdiction over their tribe. Specific BIA-operated schools can be found by the state with information about the years and material available.

First, search the state-by-state Guide to Record Group 75, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs online.

Then to request Indian Student Case Files, contact the National Archives facility that holds the records for the pertinent school. That information will be found at the link above. For example, if your ancestor attended Pipestone Indian School (1894-1959) in Minnesota, the records will be found at the National Archives in Kansas City.

When submitting a request to the National Archives, include the individual’s date of birth, as well as variant spellings of his or her name. Additional information, such as the names of parents or tribal affiliation, may be helpful in identifying a match. While the specific documents can vary widely, the records may include applications for enrollment, medical examination forms, attendance and grade reports, examples of student work, newspaper clippings, documents related to student employment, and correspondence. Photographs generally do not appear in student case files.

Military Service and Pension Records

American Indians have served in the U.S. Armed Forces since the Revolutionary War and have participated in every major conflict, including both sides of the American Civil War. They provided unique services such as being U.S. Army Indian Scouts and the U.S. Army and Marine Corps code talkers in both World Wars. Many of the older military records are digitized, indexed, and fully searchable on Ancestry.com and/or Fold3.com (subscription online services). Online access to both of these websites is free at all National Archives research facilities.

The service and pension records of these men and women can be found at the National Archives.

Prior to 1917: These records are located at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and can be requested by fax or by mail.

From WWI through today: These records are located at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, by fax or by mail.

Pictures of Native Americans

The National Archives also has pictures which show Native Americans, their homes and activities. Pictorial records have been deposited in the National Archives by 15 government agencies, principally the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Bureau of American Ethnology, and the United States Army. English names of individuals have been used, with Native or secondary designations in parentheses.

All of the pictures described are either photographs or copies of artworks. Any item not identified as an artwork is a photograph. Whenever available, the name of the photographer or artist and the date of the item have been given. This information is followed by the identification number. The pictures are grouped by subject. Tribal names as specific as possible have been incorporated into the descriptions where known and where appropriate and an index by tribe follows the list at the website.

Myra Vanderpool Gormley is credentialed as a Certified Genealogist ℠ by the Board for Certification of Genealogists (1987-2012), retired (2012).

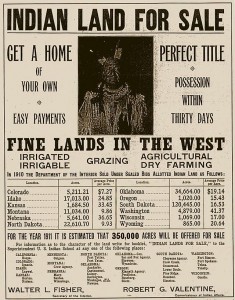

Indian Land For Sale

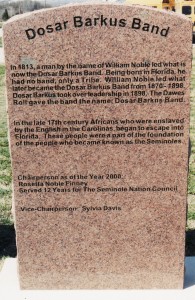

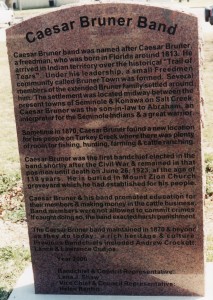

Seminole Nation Bands

The band was one of the two major elements of Seminole Society. Originally, each band was a separate Tribe which later joined with the others to form the Seminole Tribe in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Throughout the history of the Seminole Nation, the band was of primary importance to the Seminole people.

The band was the center of religious life; first with the great annual ceremonies such as the Green Corn Dance, and later with the churches. It was also the center of political and legal life. The band Chief, his assistant, and one of the band counselors from each band formed the Tribal Council. Within the band, the band Chiefs and the counselors made the laws for that band and served as a court to settle disputes within the band. The band also was a focus of economic life for the Seminole. Each band had a communal field which was worked by all of its able-bodied members. The produce of the field was under the control of the Chief and was used to feed guests, provide for orphans and the destitute, and to help with the expenses of running the band.

Through time, the number of bands has been steadily reduced, as some bands died out or joined with other, related bands. In the 1830’s in Florida, there may have been as many as 35 bands, in 1860 there were 24, and by 1879 there were only 14 bands – the current number. In 1866, two new bands were recognized. These were both Freedmen bands composed of Negroes who had been associated with the Seminole since before removal.

They are the Dosar Barkus Band

and The Caesar Bruner Band

Band membership was determined by birth and a person belonged to the band of their mother. While it was possible to change bands, this required the permission of both bands; and band membership was usually for life. Bands were frequently known by the name of their Chief and therefore the names would frequently change when a new Chief was selected. The bands were also known on occasion by their old tribal names.

The 14 band monuments can be found on the grounds of the Mekasukey Mission, south of Seminole, Oklahoma

Researching Native American Ancestry

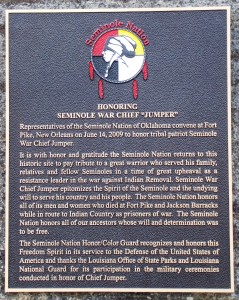

Honoring Seminole War Chief ‘Jumper’

Representatives of the Seminole nation of Oklahoma convene at Fort Pike, New Orleans on June 14, 2009 to honor tribal patriot Seminole War Chief Jumper.

It is with honor and gratitude the Seminole Nations returns to this historic site to pay tribute to a great warrior who served his family, relatives and fellow Seminoles in a time of great upheaval as a resistance leader in the war against Indian Removal. Seminole War Chief Jumper epitomizes the Spirit of the Seminole and his undying will to serve his country and his people. The Seminole Nation honors all of its men and women who dies at Fort Pike and Jackson Barracks while in route to Indian Country as prisoners of war. The Seminole nation honors all of our ancestors whose will and determination was to be free.

The Seminole Nation Honor/Color Guard recognizes and honors this Freedom Spirit in its service to the Defense of the United States of America and thanks to the Louisiana Office of State Parks and Louisiana National Guard for its participation in the military ceremonies conducted in honor of Chief Jumper.