Scattered throughout Egmont Key in plain sight are remains of its bustling past as the location of Fort Dade, built to protect the Tampa Bay area from invasion during the Spanish–American War in the late-1800s.

But hidden somewhere underground on the scenic island at the mouth of Tampa Bay lies evidence of its darker days as home to a U.S. military internment camp for about 300 Seminole Indians in the mid-1800s.

Seminoles who died there were buried without markers. No one knows how many there are.

So on Tuesday, the Seminole Tribe of Florida stepped up its efforts to find these ancestors.

Using ground-penetrating radar, the tribe’s archaeology team searched the northern part of the island near the iconic lighthouse and found areas they called “dense spots.”

Over the next few weeks, the archaeologists will process the data they gathered to determine whether these could be burial areas.

“We’ll be looking for two things: Does it have the proper dimensions of a grave and is it at the right depth,” said Domonique deBeaubien, who works with the tribe protecting Seminole remains.

Skeletons will not be moved. Rather, markers will be placed and the Seminoles will work with state officials to ensure the areas are not disturbed.

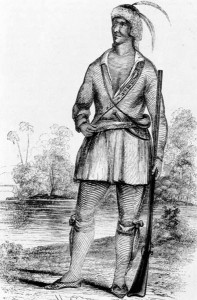

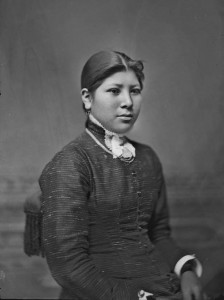

Egmont Key was a holding area for Seminoles who were being sent to reservations after they were forced from their villages in Florida.

Not all survived the wait. Some died of disease on Egmont Key. At least one is known to have committed suicide.

The island was later used during the Civil War by Confederacy blockade runners. Later, it hosted Fort Dade with its military batteries, ammunition storage, suburban-style homes, general store and even a bowling alley. Shells of some structures still remain.

Because of this past, “you never know what can be found there,” said Richard Sanchez, president of the Egmont Key Alliance, a nonprofit that preserves and protects the island’s natural and historical resources.

Sanchez pointed to a lightning fire that burned more than 80 acres of the island last July and in the process, cleared vegetation that had long hidden the remnants of former military buildings — three concrete walls of a radio-weather station and foundations for a hospital and morgue.

“I wouldn’t say we didn’t know they were there,” said Sanchez, who joined the Seminole Tribe in their search on Tuesday. “They’re documented. But they were forgotten.”

Also on Tuesday, the Seminole Tribe performed a metal detection survey of the middle of the island.

“We found some interesting artifacts from the time period the Seminoles would have been there,” tribal archaeologist Maureen Mahoney said. These include square construction rivets and a bullet believed to be from the Civil War era.

Without government permission to remove these artifacts, they placed them back in the ground and mapped where they are, explained Seminole archeology field technician David Scheidecker.

The Seminoles chose the lighthouse as a starting point in their search for burials because it is the locale of a small cemetery with 19 graves for an eclectic group — lighthouse tenders, U.S. armed forces, and five Seminoles. Only one of the Seminole markers has a name — Chief Tommy.

It’s possible, the archaeology team said, that the cemetery extended past where its boundaries are now set. The team plans to expand its search later.

The American soldiers did not respect the Seminoles enough to bury them in one place. Instead, bodies were scattered across the island and with no markings.

Some bodies may already have been washed away along with nearly 300 acres of the land the island has lost through erosion in the last century.

“We will continue to survey the island for Seminole presence and clues about what happened there,” said Paul Backhouse, historic preservation officer for the Seminoles. “For the tribe, this is a huge part of their history.”